With the colaboration of Alba Martínez Reche and Cristian Shellard

En esta página iremos incluyendo, traducidas al idioma inglés, las entradas del blog que más visitas han conseguido. On this page we will included, translated into English language, the posts most visits.

WHEN BRITANIA WAS JOINT TO THE EUROPPEAN CONTINENT

How it began

This is a well-known and repeated story. It is carried out by persistent researchers who believe in what they do, who find traces of a lost world and dedicate thousands of hours to seek if there really was a civilization or not. Their Discoveries are unique and usually change History as we know it. It happened with the discovery of the city of Troy (Greece) or with the famous tomb of Tutankhamen (Egypt). Currently the place is near the old continent, and it has been discovered that thousands of years ago the lands of Great Britain and Ireland were part of the continent. That is, there was a time when the current North Sea was a terrestrial area. Some of the first hunters, fishermen and gatherers lived there.

The idea first appeared in the 19th century, but scientific evidence was needed, which in turn came up a century later, in a fisherman’s net. It was a harpoon made by a stag’s antler. They found it in the middle of the North Sea, far away from the British Islands. After this discovery they have continued retrieving other objects which, undoubtedly, had been made by humans.

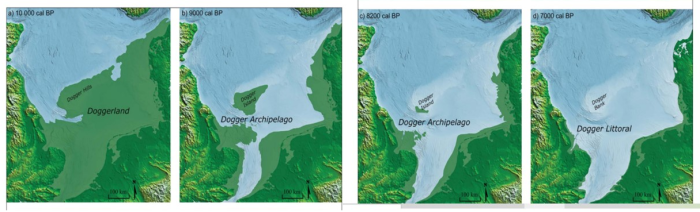

The origin of the continents has been researched, from an original mass called Pangaea, and how they were formed until the current continents took shape. However, outside specialist circles, it wasn’t known that Europe was a single continental area that over time separated into different pieces that shaped the British Islands and Ireland. After that, the North Sea came in. Nowadays, it seems to be a reality and this land, now submerged, was an area which has been called Doggerland.

Who lived there?

It was probably some sort of paradise for primitive humans, animals and plants. It was an immense plain full of woods and vegetation, with lagoons and rivers. The climate wasn’t as cold as in the north. For that reason, many species emigrated from the Highlands to Doggerland. They had abundant resources due to it being possible to fish and hunt in the different ecosystems shaped on the land. Men there were hunters and gatherers, so they had food for the whole year. It was the Maglemosian Period, at the beginning of the Mesolithic.

These conditions facilitated developing life, and soon the land was full of animal and vegetable species. The most recent studies calculate a land area between 40,000 and 50,000 square kilometres. Some researchers claim that you could walk to places now occupied by the cities of London and Oslo.

The beginning of the end

Nevertheless, this idyllic situation changed when sea levels started to rise (a metre each 100 years approximately due to the thaw), and, especially when in a few decades it raised more than half a metre, flooding the lowest part, which created different islands in the formerly attached area. Fishing became one of the most needed survival skills, for that reason small canoes and tools such as harpoons have been common findings.

The end came when an enormous landslide on the Scandinavia Peninsula (Storegga’s landslide) caused a massive tsunami that devastated life in the small islands, and many of their habitants died. The survivors emigrated to safer continental lands.

After the cataclysm, a gigantic sea with hardly any space between, the European continent and the British Islands separated even further. Thousands of land kilometres had been drowned by the Northern Sea, which increased the sea’s size, and made the scenery look similar to our actual scenery that we have today. The ancient habitants kept fishing and sailing, but from safer lands, whether in the continent or in the recently created islands.

Video of a guided tour through the exhibition ‘Doggerland’ at the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden

More information

GAFFNEY, Vincent L.; THOMSON, Kenneth & FITCH, Simon (ed.). Mapping Doggerland: the Mesolithic landscapes of the southern North Sea. Archaeopress, 2007.

NYLAND, Astrid; WARREN, Graeme & WALKER, James. When the sea become a monster? The social impact of the Storegga tsunami, 8200 BP, on the Mesolithic of northern Europe. En EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts. 2021.

SPINNEY, Laura. Searching for Doggerland. National Geographic Magazine, 2012, 222, 6, p. 132-143.

WALKER, James, et al. A great wave: the Storegga tsunami and the end of Doggerland?. Antiquity, 2020, 94, 378, p. 1409-1425.

WENINGER, Bernhard, et al. The catastrophic final flooding of Doggerland by the Storegga Slide tsunami. Documenta Praehistorica, 2008, 35, p. 1-24.

TEREDO NAVALIS: THE WORM THAT KILLED THOUSANDS OF SHIPS

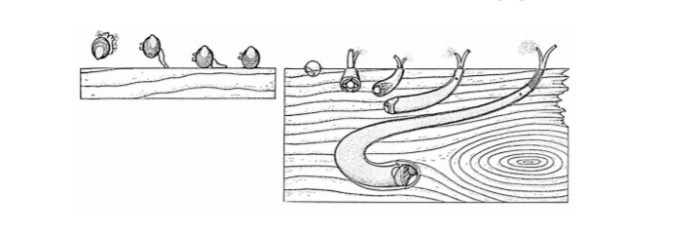

There has always been fear of the seas. For centuries, gigantic sea monsters stole the dream of the sailors, but it was a small creature the causing of the most disastrous and the most dangerous issues: a “worm” who ate the wood from the vessels. It ended up drilling the hull until it was useless for sailing, and when this happened in the middle of the sea, there was no possible solution. If it was detected at the port, they could check if the damage was general, or it was only affecting a part of it. In that case, it could be replaced. In Spain, they called it broma, “joke”, although it was a serious problem.

More about the driller

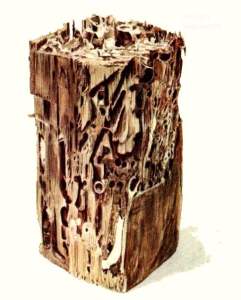

The “shipworm” Teredo Navalis is one of the most effective and harmful marine invaders. It isn’t actually a worm, but a mollusc, specifically a drilling head lamellibranch bivalve. It is an embedding animal that opens long and demolishing galleries of woods’ the underwater side, trying to devour the cellulose inside. It can reach up to 20 centimetres on the adult phase.

It is still unclear if it came to Europe from the Asian southeast, or if it was born in Europe and, from there, it invaded the rest of the world. A few years ago, Teredo reappeared at the occidental Baltic Sea, where it caused damages estimated between 25 and 50 million euros along the German coast. Teredo reproduces extremely fast and can resist adverse climatic circumstances.

Testimonies

Distinguished sailors as Columbus had to fight hard against the invasion. During his fourth trip (1502), all his vessels were drowned due to the damage caused by the Teredo Navalis. On his diary, he wrote that his vessels were:

“…rotten, eaten away… (…) more riddled than a beehive. With three bombs, pots and boilers, and with all hands at work, they couldn’t hold the water coming to the vessel, and there wasn’t any other remedy for the chaos the worm had caused (…)” from Columbus’ letter: “my vessel is sinking below myself…” (source).

The same thing happened during the first trip around the world with Magellan and Elcano.

Pirate Francis Drake had to anchor at the California coast to make repair to his vessel, The Golden Hind, drilled by the sea worms.

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, an Indian chronicler, suffer and narrated it in 1523, while he was travelling from de Port of Saint Mary (currently in Colombia) to La Española (currently Haitian and Dominican territory). The vessel, a caravel of his property, “was so drilled because of the broma” that it was drowned in the middle of a rough sea while the crew, including him, was trying to cover the holes with their shirts.

This situation led many people to try finding a solution. Some were effective, although temporary, and some were just tricks to make money (Trueba 1987).

The invasion

Despite that some tried to develop methods against it, there is still no easy solution for the shipworm problem. The way of avoiding them was covering the wooden hull with metal sheets. Also recovering it with repellent substances. However, this protection stopped having effect soon after. The last chance, if the invasion hadn’t affected the vessel’s hull excessively, was getting into river water (as the Seville’s river) for the sweet water to kill the Teredo. Nowadays, it still lives in mussel fishing boats and breakwater fishing boats.

Teredo doesn’t attack every wood the same way. For instance, is tougher, so it is harder to drill it. There were exotic woods, some from the American continent, which seemed to be more resistant. For that reason, those, such as Mulberry, Camphor, Brazilian orchid tree, Camphor and Laurel were preferred for naval construction (Figueroa, 1996).

More information

CURT MARTÍNEZ, José. Navegando en una sopa de seres microscópicos. Revista General de Marina, 2015, 268, 2, p. 299-314.

FIGUEROA, Guayacán y SÁNCHEZ, Fernan. Contribución al conocimiento de los organismos. Acta Oceanopacífica del Pacífico. 1996, 8, 1.

HOPPE, Kai N. Teredo navalis—the cryptogenic shipworm. En: Leppäkoski E., Gollasch S., Olenin S. (eds). Invasive Aquatic Species of Europe. Distribution, Impacts and Management. Dordrecht: Springer, 2002, p. 116-119.

MOYA SORDO, Vera. Entre la vida y la muerte: averías, tormentas y naufragios. Manifestaciones de miedo durante los viajes atlánticos ibéricos (siglos XV-XVII). Boletín de la Academia Nacional de la Historia (Venezuela), 2010, 93, 371, p. 127.

TRUEBA, Eduardo. Dos experiencias contra la » Broma» (Teredo Navalis), en la Sevilla del siglo XVI. Revista de Historia Naval, 1987, 5,16, p. 83-102.

WEIGELT, Ronny, et al. First time DNA barcoding of the common shipworm Teredo navalis Linnaeus 1758 (Mollusca: Bivalvia: Teredinidae): Molecular-taxonomic investigation and identification of a widespread wood-borer. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 2016, 475, p. 154-162.